'I wanna be a supermodel'

'Cause I'm young and I'm hip and I'm beautiful. Everyone will want to look just like me. Wait and see. When I'm a supermodel.'*

In October 1995, Cher Horowitz ‘whatevered’ onto the screen to the tune of Jill Sobule’s Supermodel. Aged thirteen, I wouldn’t see Clueless until months after its Region One release. Living in Indonesia in a pre-internet age, we needed to wait for the LaserDisc in order to partake in the North American cultural zeitgeist.

The film epitomised everything I wanted to be when I grew up, sans irony. I’d yet to read any Jane Austen, so I didn’t know Heckerling based her screenplay on the 19th Century Emma. The Beverly Hills script featured real teenagers (not pre-teens like me and my friends), and the three-year gap catered to me perfectly: young enough to imagine myself in those shoes and that outfit, and not old enough to seem tired or out-of-reach. Each scene detailed a moment in which I’d find myself playing centre stage, surely, by my sixteenth birthday. With the glossy sheen of late 20th Century films, you’ll find no gritty Fast Times At Ridgemont High here: this was all bubblegum and blonde highlights.

I could probably write at least six Substacks on the concomitant issues evoked from this one film. But here I’ll focus on three myths that I immediately bought into and believed would come true.

And how a part of me is still (kind of) waiting.

Dion and Cher at their Beverly Hills High School in Clueless

Can you see me now?

1. The Myth of Being Discovered

From the first time I took the stage in a community acting class at age eight, I began preparing for the moment I’d be discovered. This hope, wavering somewhere between expectation and desperation, stayed with me for decades. The scoop would both validate my unmatched talent as an actor of stage and screen (forget that I had no on-camera experience), as well as grant me the unqualified admiration of thousands, millions, of adoring fans.

At its most simple, my discovery would follow the arc of the child star plucked out of obscurity. Rather than a Penelope Tree-style spotting, I hope for more of an Edward Furlong-type recruitment.

Penelope Tree writes in her interview for The Big Issue:

‘At the close of 1966, in my last year of high school, I was spotted by photographer Richard Avedon at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in New York. Though I was an insecure, introverted 16-year-old, Avedon and Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland inspired me to come out of my shell. Within months I was modelling for Vogue and other American magazines.’

Penelope Tree by Richard Avedon

Even I knew my circumstances wouldn’t land me anywhere near New York, let alone at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball. But I could hold out hope that a talent scout would find me hanging out at the Pondok Indah mall, or maybe on a bike ride in the Canadian suburbs when I stayed with my aunt and uncle in the summer. This felt plausible to me, as Edward Furlong — who I’d only recently been allowed to watch in Terminator 2: Judgement Day — had been plucked from obscurity in a Boys’ Club in Pasadena, California.

Pre-internet, pre-Instagram and pre-influencer, the only way I could aspire to be seen beyond the small sphere of fairly-functional family dynamics was magazine- or movie-stardom. Believing I’d be discovered and catapulted to fame served two of my deepest needs.

The first: to be so special, so electric, that it would be impossible to go unnoticed. I can see this as either a delusional shortcoming or a totally rational worldview. Delusional because I was not particularly academic, or talented, or dedicated, or gorgeous, or tall, or slim, or well-connected. But rational because I was (am) privileged, white, able-bodied, intelligent enough to apply myself to tasks and succeed. So why not this task of achieving fame? This mixed with the naïveté of believing myself deserving of accolades completely bereft of effort. A belief which, sly and quiet, would follow me into adulthood.

The second: that I needed accolades and adoration from hundreds, thousands, of people to prove my likability, if not my ability to be loved. This misplaced longing erupted from a misunderstanding of the affection I’d gleaned from my family, friends and teachers. I assumed the attention I received from them was only the beginning, that there was more, that love moved in one direction: towards me. That these sensations of approval would only grow ten- and one-hundred-fold. A misplaced, wild and intoxicating extrapolation of what it meant to be totally adored.

‘I want to be 5’10’’ like Cindy Crawford’

2. The Myth of Being a Supermodel

In Clueless, Cher quips this quote after eschewing a thermos of coffee, explaining that caffeine will stunt her growth. Crawford was another discoveree: in 1982, while working during the summer detasseling corn on a nearby farm, she was spotted and photographed by a local news photographer. I deduced: if I avoided coffee, hung around riding bikes and acting in community am dram, I’d be discovered. My next step: to prepare for my audience.

Today, I’d be posing with my arm uplifted, tilting my iPhone as I gaze up at the lens, my halo light smoothing out my pores and lifting shadows. But in the 90s, all I had was a push button camera and some white sheets.

My friends and I would strew clothes across my bedroom, make up outfits we’d never wear and copy models’ poses from Seventeen magazine.

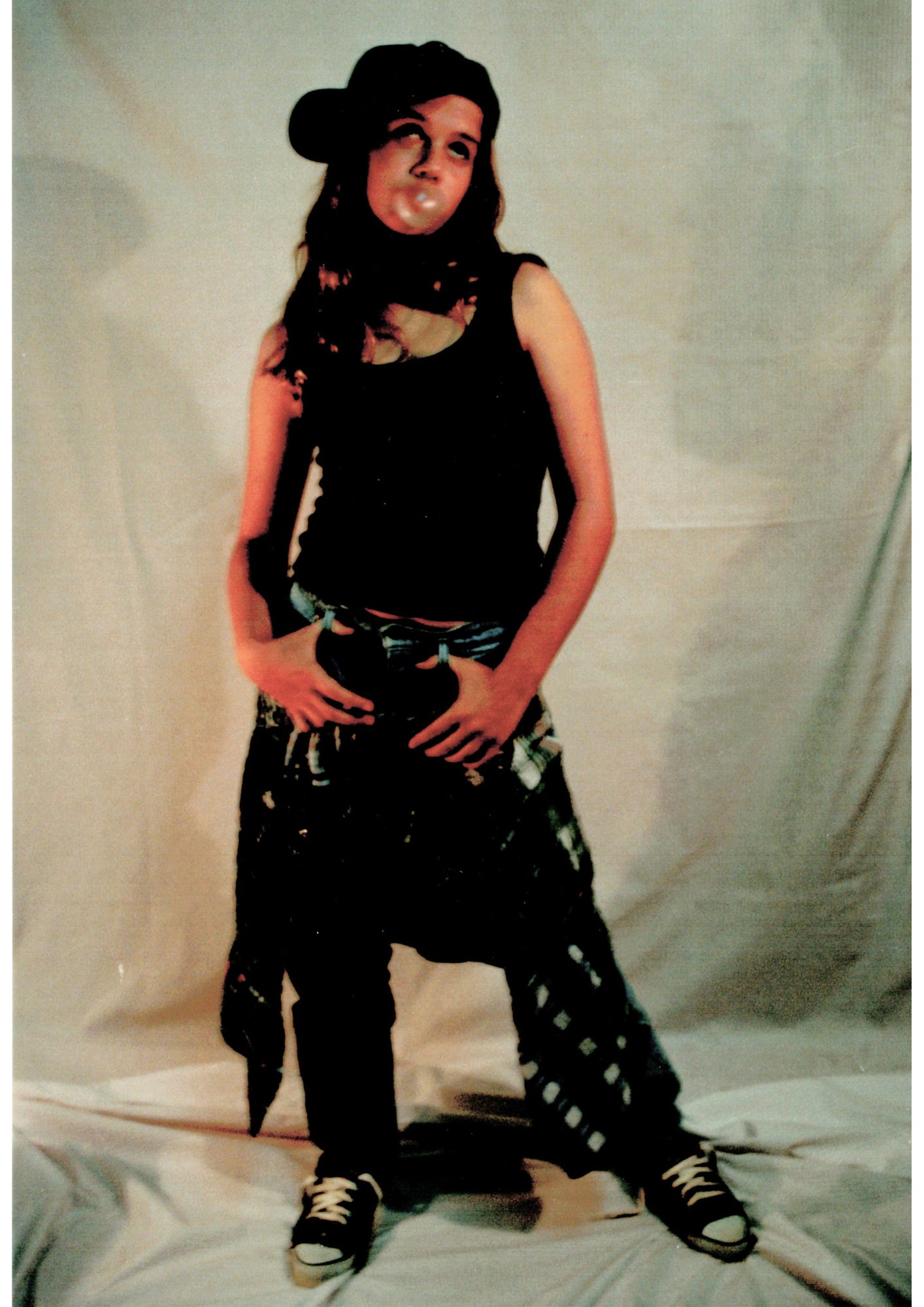

Author’s archives

I learned the bits of my body I unabashedly loved: my naturally highlighted curly hair and the blue of my eyes.

When I'm a supermodel

And my hair will shine like the sea.

Everyone will wanna look just like me.

And all the ones I didn’t.

Without the immediate feedback of a digital camera, we had to wait to develop the film to see if we’d nailed our focus, light levels and exposure. Whether we’d struck the right pose or gazed suitably pensively into the lens also remained to be seen.

If I could figure out how to do it right, then I’d be admitted into the game. I’d be allowed to play. Nevermind my lack of connections, training, propensity to sit still or my decidedly-not-supermodel height or proportions.

I really wanted to believe what Crawford said in the 2023 documentary Super Models: ‘It wasn’t about the look or the fashion — it was about the women.’

Was it really, though?

That’s the hook, for sure. That is the balm that cools the fevered feminine question. If we believe our actions, our fashion choices, our triumphs, are in the service of women, then that’s allowed. And yet: I am dubious.

The documentary frames the stories of Cindy, Linda, Naomi and Christy (no last names needed) not as triumphs of fashion, but of women who broke free from rules and stereotypes. These four have undoubtably found success and personal freedom. But has the freedom they talk about resulted in emancipation for all women? Or have they simply taught that, in order to be truly free, you must win in all the ways these women have done.

Their personal moments of realisation are worthy of respect. Four fortunate women, their victories are hard won. But we can’t transmute their individual experience into a shared arena. If the pay rise of any one person, or the representation of another skin colour or ethnicity, only serves to sell more products or increases the freedom of that single individual, then there is no emancipation to be had. There are no spoils to share. There are no rights to be heralded.

A moment, and then poof: it’s gone.

Where’s your thigh gap?

3. The Myth of Achieving Body ‘Perfection’

My teenage modelling sessions led to us sharing direct feedback about our bodies. As we swapped clothes, we realised some outfits couldn’t be shared: one waist did not equal another. Judgements and overheard advice crept in: ‘Your thighs shouldn’t touch’ my friend explained as we pulled on our swimsuits. But my thighs had always touched. In fact, I couldn’t remember a time, even as a child with semi-spindly limbs, that they had not.

Even with belly-button crop tops and exposed legs, actors Alicia Silverstone, Stacey Dash and Brittany Murphy look positively wholesome compared to the sculpted 21st Century bodies we now scroll past each day. Throughout Clueless, Cher dispenses disordered food and diet advice (from making juices to instructing Di to cut food into smaller pieces to help lose more weight). And while I didn’t buy a juicer or give up crisps, I did start waking up early to swim before school. Then, I stopped when my friend told my swimming doesn’t burn calories because you can’t sweat in the water. I cut out a one-panel cartoon of two women working out, one saying to the other: ‘I do have abs of steel, they’re just covered in jello.’

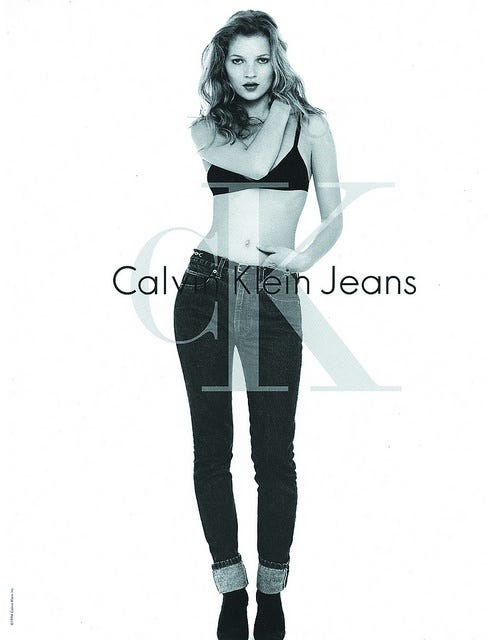

Another body image ideal made its way into cultural consciousness circa 1995: the androgynous waif, featured prominently in CK One adds. The star of the show? Kate Moss — slim, heavy lidded and possessor of a measurable thigh gap.

Kate Moss for Calvin Klein

My ruminations on body image and weight will certainly feature in future editions. The particular angle here focusses on my nascent belief that my weight and body shape had a clear bearing on whether I’d be seen, noticed, approved of and accepted.

‘I didn't eat yesterday,

I'm not gonna eat today

I'm not gonna eat tomorrow

Cause I'm gonna be a supermodel.*

Always, I wished I could trade everything between my armpits and my knees. I wanted larger breasts, a flatter stomach, and smaller thighs. I learned and practised the habit of dissatisfaction: internally, within myself, and externally, in how others viewed me.

More from Penelope Tree:

‘As a model in the 60s, I was no one unless I was thin, and I was always on some kind of extreme diet. Then at 22, I suffered a bout of late-onset acne brought on by a hormonal imbalance caused by my eating disorder. The acne was so disfiguring it put a halt to my modelling career. I lost my self-confidence completely and it took a long time before I recovered from the depression caused by my ‘loss of face’. My identity was completely caught up in being a model and what I looked like.’

Whilst I now accept I will never weigh less than 130 pounds, let alone less than 100 — I can never completely train my eyes not to track to my waist when I look in the mirror. To notice when my jeans button tighter after a cold winter of less movement. To eat to satiate hunger or to indulge in pleasure — without the kickback of guilt, of wondering at the consequences.

Not so young, not so hip — but here

So now I’m not so young. Certainly not hip.

Here’s a summary of what I haven’t done:

Become a supermodel

Been discovered by an agent, photographer, casting director or model scout

Grown to 5’10’’

Developed a thigh gap

The list seems ridiculous, ironic and tongue-in-cheek. But underneath each unrealistic tick-box is a less fathomable longing. The desire to be unique, singled out: achieving a status above my peers. The wish to be seen. To be witnessed by one person is connecting and divine. To be observed by thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, tricks me into believing I will feel a million times the connection.

When I let go of the idea that I need to pose for the camera, I move into sensation: I feel my body from the outside in.

When I drop the numbers, the measurements, the height and the weight and the waist size, I find freedom to flow and fluctuate: with seasons, with energy levels, with light levels and times of sleep.

When I gaze deeply at myself, in the mirror or in meditation, I am fully witnessed. The love of those around me goes both ways; it does not belong to either of us. I do not need to earn or win it.

Searching the internet for this post, I found an alternate version of the Supermodel lyrics. Rather than: ‘I'm young and I'm hip’*

I found: ‘I’m young and I’m here’*

Here. Definitely, defiantly, here.

Author’s archives

*From the song Supermodel, written by David Baerwald, David Kitay, Brian MacLeod and Kristen Vigard for the soundtrack to the 1995 film Clueless.

Love your writing. I'd love to share it on my notes Suryadarshini but not sure whether you wanted it to be shared just yet.

As always I delight in your eloquence and evocation of your experience, in a way which transcends the personal. For me it brings to mind the emperors new clothes and the courage to name the stories and societal constructions which bind us. Thank you again :-)