Maybe someday my name will be in lights

My childhood dream to be an actor got me to my first university audition. When I wasn't cast...I gave up. What do we do when a dream dies? And how long do we wait before we resurrect it?

‘I need your help,’ he said. ‘Will you read with me?’

We sat next to each other in the circle, listening intently to one person after another read their words. When his turn came, he asked to play the second part in the climactic scene of his Act III. I looked over his laptop, not having read the words before, with only a cursory understanding of the plot and characters.

‘Any notes?’ I asked.

‘Nah,’ he replied, ‘let’s just do it’.

As we reached the apex of the scene — two siblings accusing each other of their respective callous responses to their father’s death — I felt that familiar, though long-lost, frisson. Slipping into a character, feeling the ripples of their joys and sorrows, the swell of their habits, their history and their relationships, erupting now in this exchange, in this moment. Connecting with your scene partner, topping their lines, cutting in as you build into the argument, only glancing at the script even though you haven’t seen it before. And the audience, rapt, all the focus of the room on the two of you.

Electrifying, unifying, riveting.

After my last line, a beat.

Then applause.

Have I seen you on screen?

At dinner, someone turned to me, ‘So, did you train as an actor?’

And another, ‘You should definitely act.’

The euphoria of it. And the ache.

Of course I wanted to be an actor. An actress, I’d say in the 90s. My mom enrolled me in community theatre at the age of eight, and I hung out on stage, sometimes as a extra, occasionally with a line or even a scene of my own, nursing dreams of being discovered while hanging out with my sister in suburban Canada.

Finally, in high school, my breakthrough role: starring at Petruchia in a gender- reversal production of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. I took drama during school hours and got driven downtown once a week for classes at Theatre Calgary. I memorised lines, workshopped scenes, but mostly turned up for rehearsals and turned on my charisma. I can’t claim much craftwork, or blood or tears. I received recognition from my peers and my parents, and that was enough.

My privilege had taught me how it worked thus far: you decided you wanted something, you showed up, and you got it. Sure, there’d be some hard knocks — everyone said that. But this is what I’d imagine I’d do. Just like that.

Two years later, I arrived at university, enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts programme. My first year schedule held a smattering of introductory courses, including Drama and English, with plans to audition for the Bachelor of Fine Arts in my second year. I could also try out for roles in extra-curricular drama productions, which I duly did, ready for my big break.

On the day of the audition, I came into a high-ceiled room with a sombre man in black-rimmed glasses. After I performed my monologue, he asked me to improvise some scenarios that he seemed to come up with on the spot. He tossed them out to me, asking me to pivot characters and scenarios mid-scene. The only one I remember, these decades later, was being told my friend had just jumped off a roof: I ran across the room, screaming dramatically ‘Nooooooo……’ and ending in a crouch beside the wall.

My name did not appear on the casting list.

It slowly dawned on me that many of the other teenagers here had also starred in their high school plays. Had prepped and rehearsed for their audition, too. That some might be more confident, more talented and certainly more committed than me. How, if I wanted this life, I’d have to work at it.

And so I gave up, just like that.

Why I couldn’t do it then

I meandered through the rest of my first year at uni and returned for a second, but not a third. After my acting class wrapped in the first semester, I never took another.

How had a dream I’d nursed for over a decade vanished so quickly? I have some theories.

1. Effort, rejection and resilience

At the time of this audition, in the autumn of 1999, I was 17 years old. I’d been raised on a childhood of encouragement and reward: I showed up, I did stuff, I got the gold star. Yes, I ‘worked’ at school, but as long as I put the time in, my assignments received accolades (English, Drama) or satisfactory marks (Physics, French).

I rarely did a second draft. If I did, it was a recopying of what I’d already written in neater script. I didn’t really believe I could improve on my initial work. I didn’t know how to make an effort to overcome a challenge.

In my after-school dance classes, I stayed at the level most comfortable for my skill set. Sure, I had to practise and learn the steps — but that was about it.

I didn’t have the psychological maturity to process rejection. If someone said: ‘There are ways this could be better’, what I heard is: ‘you’re not good enough’. And I didn’t know what to do with that. So I’d just quit.

2. Non-existence and the need for oblivion

The stories I could tell you about my teenage drinking won’t shock you. From the outside, I looked like any kid arriving at university and discovering freedom: drunken dancing, inebriated sex, shots of tequila, beers when I should have been studying, vodka and Sprite out of a straw.

But very quickly I started practising a new way of drinking, one that had less to do with fun and freedom and more to do with aloneness. I drank to blackout so I didn’t have to remember what I was doing; I got a job at a bar so I could keep the cost of my habit low and normalise being slightly slurred by the end of my shift.

Before I got sober four years later, I’d fallen much farther. But for this essay, I’m reflecting how alcohol affected my motivation. I leaned in to the mediocrity. I didn’t need to be great — I just needed to get by. As long as I could maintain the status quo, I could get to my classes, get to work, get to the end of the day, and not think too much about the next one.

To carve out time for a craft, to refine my skills, to work with talented people and up my game, to lay it on the line again and again, with no back-up plan, would have required all the energy, tenacity and verve available to my seventeen-year-old self. And I was in no state for that.

3. Reality-checks, cynicism and fear

Before my tenth birthday, I told my dad I wanted to be an actress. He said: ‘because you love to act, or because you want to be Julia Roberts?’

A beat.

‘Well, yeah, I guess it’s to be as famous as Julia Roberts.’

He shook his head. ‘You’ve got to do it for the love of it, otherwise you’ll never be happy.’

He wasn’t wrong.

I don’t want to misrepresent him: Dad was encouraging. He came to all my plays and dance recitals. He okayed me going to uni with an eye on a Bachelor of Fine Arts (he was paying). But he always encouraged me to have ‘something to fall back on’. A chemical engineer who’d made his money in oil and gas, he knew if I chose to follow in his footsteps, I could be successful: with hardly any women engineers in the labour market, as long as I got good marks I could chart my own career.

Except I hated physics. And chemistry. And I only like abstract math, when all the numbers were integers and x = 3 at the end of a quadratic equation.

But I got his point. By the time I was ten, adults stopped smiling indulgently when I said I wanted to be an actress when I grew up. They’d smirk slightly, or say, ‘Mm hm, and what’s your plan B?’

I never made one. I gave up on Plan A (the acting), briefly pursued a Plan B (Bachelor of Arts with a Major in…never to be determined), then dropped out of uni and headed out into the real world, first backpacking and then working in corporate Calgary. As a way to rationalise my choices, I taught myself to scoff at anyone pursuing their ‘dreams’. I congratulated myself for already seeing through the naivety that still fuelled their futile attempts. I was so certain I had it all figured out — despite the fact I'd just turned twenty years old.

Why I don’t want to do it now

Every few years over the past two decades, when I’m switching roles or pondering my next career change, I wonder if Now Is The Time. Whenever someone says: ‘What would you do, if you couldn’t fail?’, I think: ‘act on Broadway’. Or they ask: ‘What lifelong dream have you still to realise?’, I respond: ‘star in a Hollywood film’.

A few years ago, I read Designing Your Life, by Bill Burnett and Dave Evans. They run a course at Stanford University on Life Design, applying tech design principals of iteration and ingenuity to designing your perfect professional life.

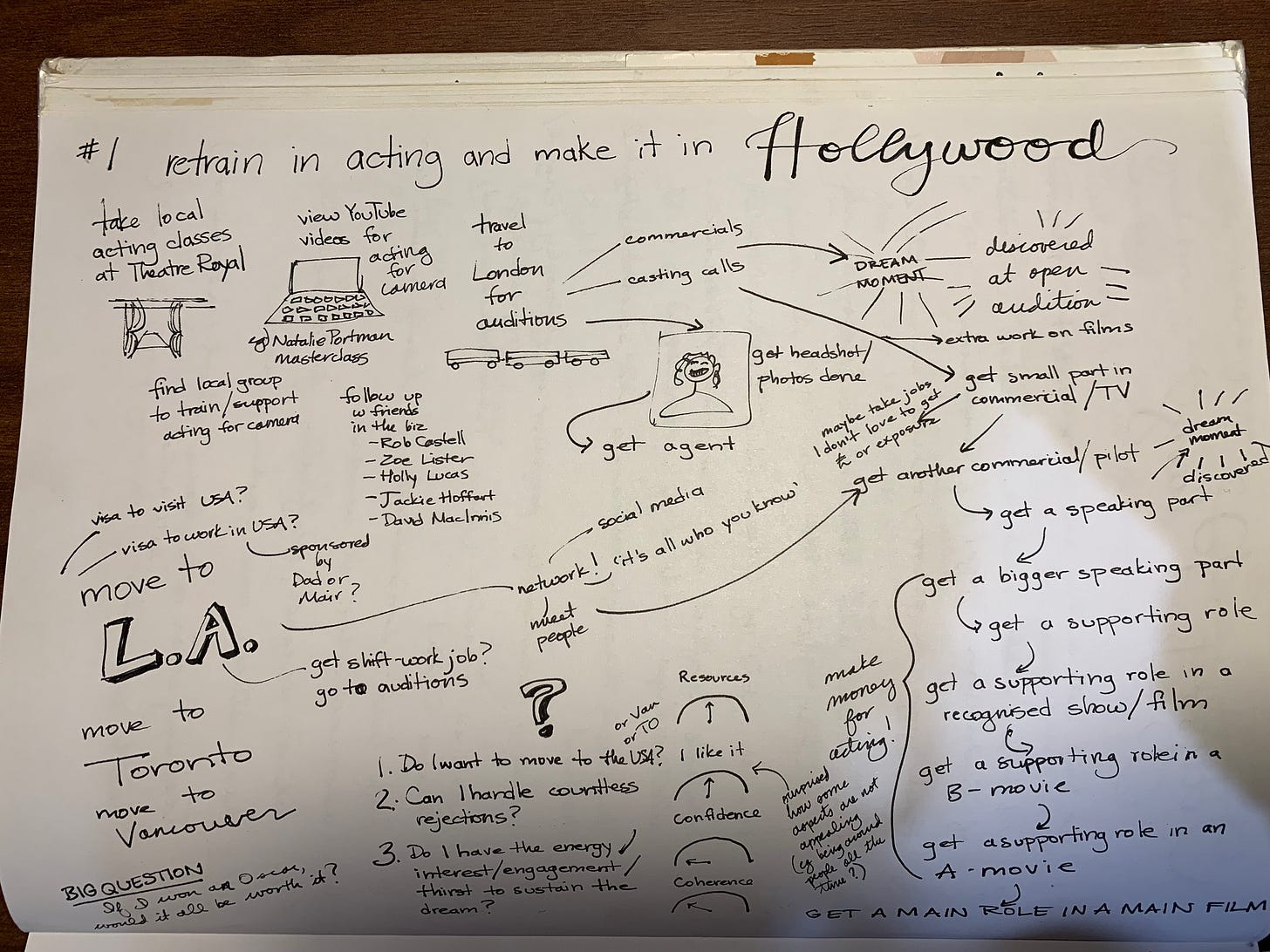

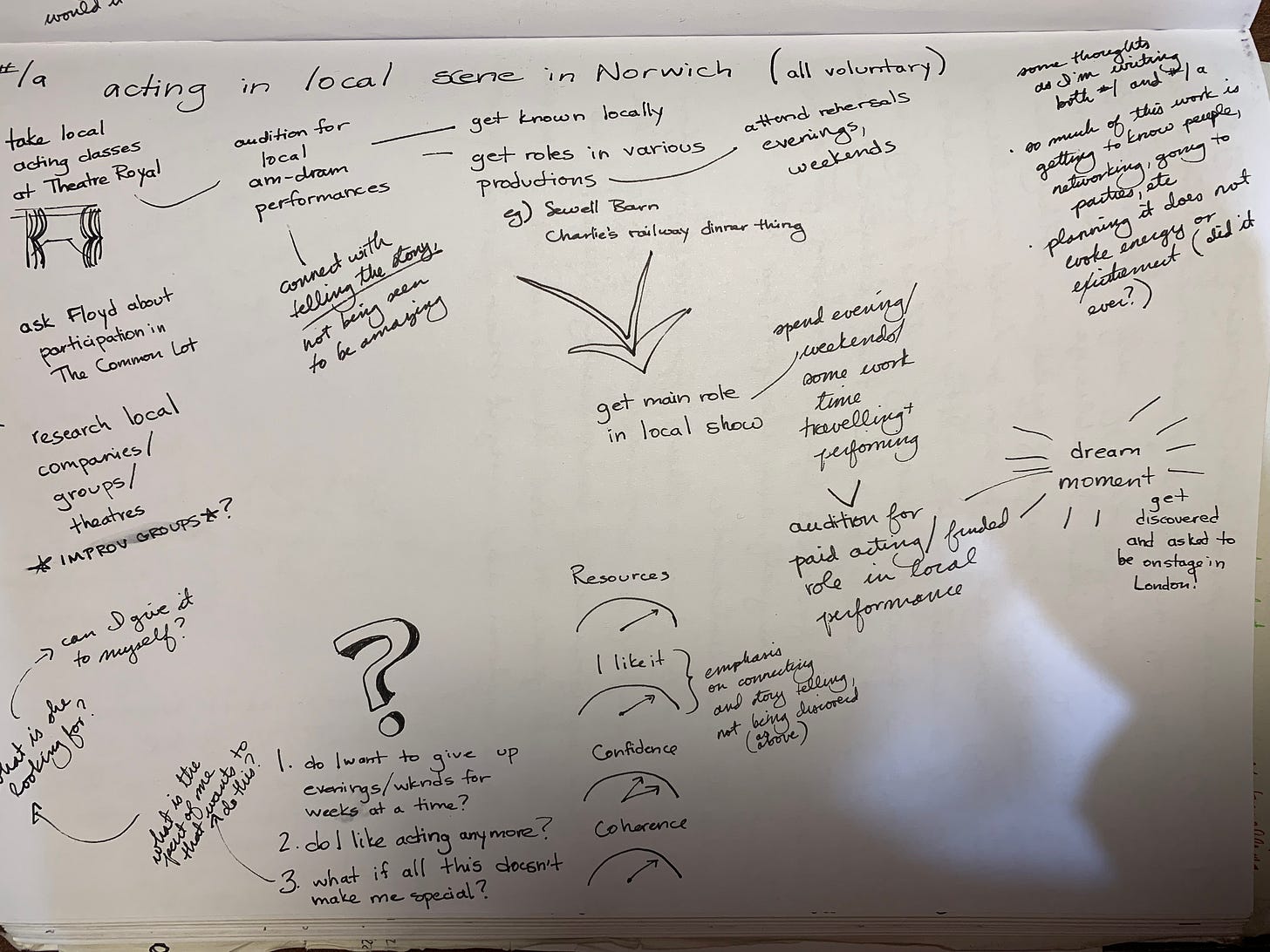

One of their exercises encourages you to map out your dream career. You rate how excited you are about it, how feasible it is, and what steps you need to take to realise it. Here’s my map for ‘becoming a world famous actor’.

I remember the feeling of drawing and writing this out. How instead of lightness and possibility, I felt weight and sluggishness. How the reality of this life is not a frisson of connection on a stage under bright lights. It is countless hours of sitting on uncomfortable chairs waiting for your name to be called. It is self tapes and head shots, shopping for representation and reframing rejection as one ‘not yet’ after another.

I don’t want an actor’s life. I don’t want to move to London, or commute there, to attend auditions. I don’t want to sign up for acting classes where we massage each other’s shoulders and train in the Stanislavski method.

Even more than that: I don’t want to dedicate hours over weeks and months to an am dram production at my local theatre, performing for a handful of kindly smiles. The time commitment (which I remember from my community theatre days) requires hours of cast bonding, table reads, rehearsals, and then tech and then dress and then two nights of a show to a room filled with family friends.

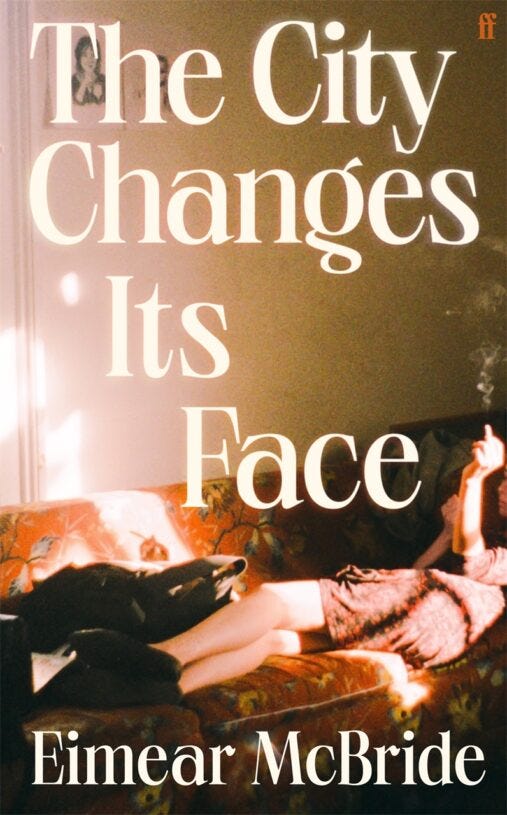

Instead, maybe I can use some of these transferrable skills. Eimear McBride, with a just-published new novel, ‘The City Changes Its Face’, is a Stanislavksi-trained actor. At the Assembly Rooms in Norwich on Thursday evening, she answered questions on the intersection of acting, writing and film.

When she started writing, she says, she used what she learned as an actor to create a character from the inside. ‘I know how their past comes with them in their bodies. When you create a character, you find parts of you that connect to parts of them, in a reality you understand.’

She uses language to create the character, seeking to ‘give the reader that intense experience of watching a drama or film. I am aware of the reader — even if it is tricky for them to get started, I want them to know [the writing] is there for them.’

This connection between the actor and her audience, and the writer and the reader, is bi-directional and communal. It is not one way.

‘An actor isn’t doing this to entertain the audience, but they are doing it for the audience. It needs to be available to them, even if I’m asking a lot of them.’

Perhaps this is the truth of why I couldn’t pursue my acting dream: I couldn’t see beyond myself. I craved the applause, the attention, the success — for me, only. I sought connection with the audience only so they could reflect back their adoration. I didn’t want to come into relationship with them — I only wanted it one-way.

My years of scene study, rehearsal and performance serve me well. I love being up front: whatever you need said to a room full of people, I’m your woman. Getting to know characters from the inside means I can forge an imaginative, empathic connection with almost anyone — fictional or real life. And maybe after all these years, I’m finally starting to learn the mutuality of connection.

I will always jump at the chance to perform. To read a scene, to sing a song, to be at the centre, under the lights. I’m not interested, however, in the other 95%: the auditions and the self-promotion and the comparison and rejection. I’m forty-three now, and I don’t have the energy.

But if you know anyone looking for a lead for their West End show, please do let them know I’m available.

DM me for my number.