The erroneous link between effort and achievement

The story we're told: if we make the effort, we'll receive the reward. Unfortunately, it's a lie. Instead of continuing the delusion, we must develop courage to make effort for its own sake.

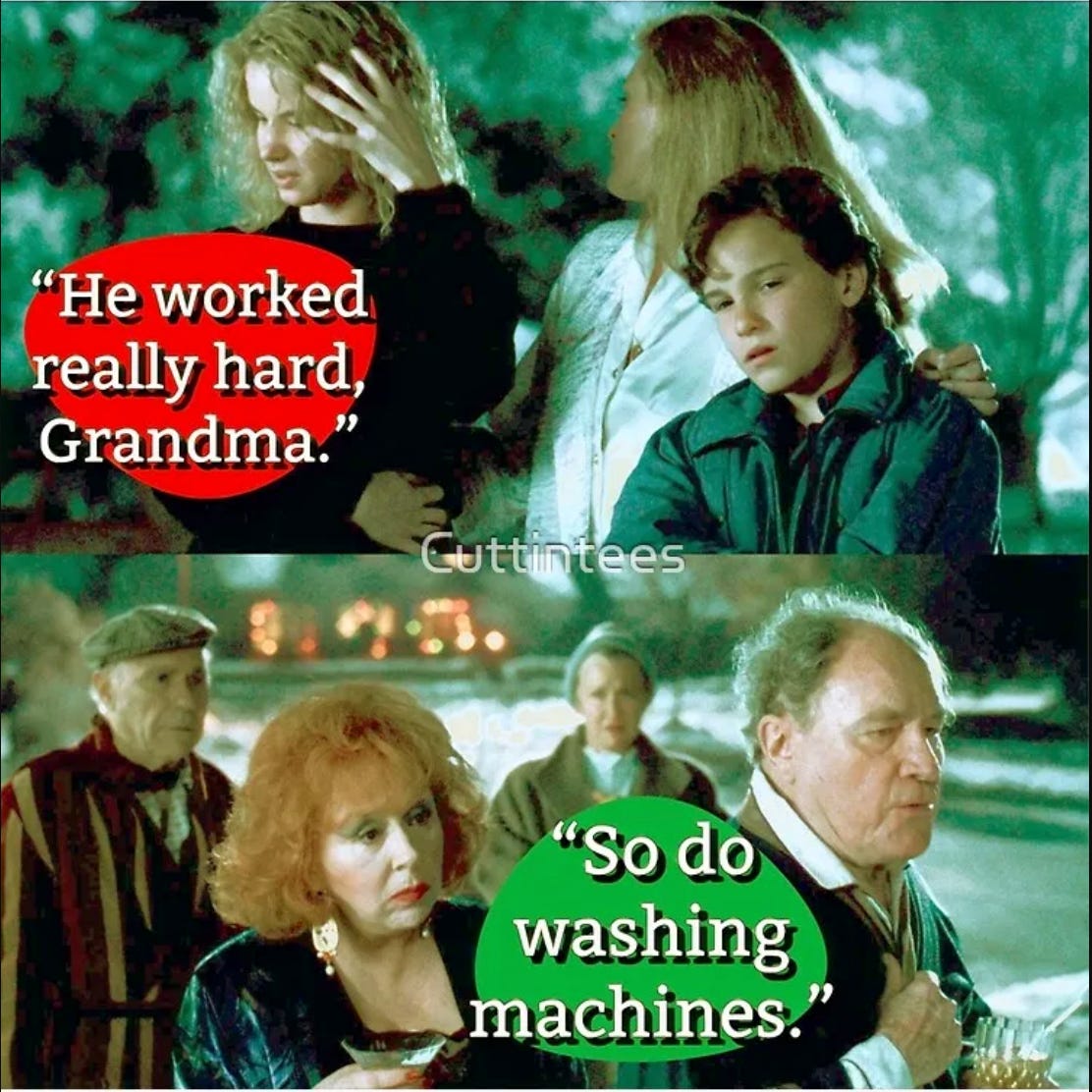

In the 1989 film National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, Chevy Chase gathers his whole family, including in-laws, onto the front lawn in subzero temperatures. They’ll witness him switch on all the Christmas lights he’s spent hours affixing to every square inch of his house. He’s toiled under moonlight, neglected his marriage and strong-armed his kids into helping (‘You want something you can be proud of, don’t you?’ he says to his son).

They’re standing with their arms wrapped round each other for warmth, showing begrudging encouragement, humouring him by making drumroll sounds.

He flips the switch.

Nothing happens.

As he frantically checks his hand-drawn diagrams, tracing his electric circuits and plug socket pathways, his mother-in-law sips a martini and rolls her eyes.

‘I hope you kids see what a silly waste of resources this was.’

His daughter defends him: ‘He worked really hard, Grandma.’

But his father-in-law deals the final blow. In a monotonous voice, disinterested in argument or discourse, he delivers his retort, decisive and final.

‘So do washing machines.’

‘I always knew you would’

In my current job, I write fundraising applications. Each document represents hours of meticulous work: crafting precise language, rearranging paragraphs and structuring justifications for our funded projects. I hope most of them are read, but there’s no way to know. What I do know is that fewer than 20% of them have resulted in a successful grant.

In my previous role, I was hired to run a multi-partner project with high output deliverables. By the end of the first quarter, we’d already fallen behind our milestones. At the halfway point, I knew we’d never hit our targets. In the third quarter, my CEO explained how this position had been created specifically for this project — and if the project didn’t continue, neither would the job. Six months later, that proved to be the case, and I accepted a demotion in order to stay employed.

When I received my Buddhist ordination, I expected I’d take up positions of leadership in my community — delivering teachings and supporting newer members. But after individual challenges in my practice, I couldn’t step up the way I imagined. Speaking to a friend over coffee last week, I reflected over the past nine years, and how much more involved I am at the moment — in fact, from the outside, someone might say I was an engaged member of our spiritual community.

‘As I always knew you would be,’ he responded kindly.

But I did a double take. ‘How did you know?’ The subtext being: he, or anyone, couldn’t have. To claim that he did is erroneous, and to pretend he could see the future struck me as illusorily superior1.

Because he’s my friend, I told him this. And together, we interrogated his assumptions. What he could have said was: I’m your friend. I see your efforts, your commitment to truth and connection. We stay in contact with each other on the basis of that commitment. I am with you.

He laughed as he admitted: ‘To say I ‘knew’ about the outcome assumes I have some kind of omniscent viewpoint, and also exaggerates the impact I can make on your life.’

As we broke down this view even further, I realised that we’d entered the territory of conditionality. Rather than assume any of us — whether the actor (in this case, me) or the observer (in this case, my friend) — can cause or even sway an outcome is to overestimate our abilities. We cannot cause any particular event to occur. We can, however, acknowledge the effect of our actions, efforts, conversations and relationships. But these are two separate categories: causal effect and conditioned effect.

Even with the very best and sincere effort on our part, it need not follow that the expected result will materialise. Many factors, which are totally out of our hands, go to produce the results. The action may be in our hands but the results never! Our sorrow and suffering comes inevitably from the fact that we expect certain results that seldom accrue.

— from Nitya Yoga by Vanamali

It’s the expectation that causes suffering. The suffering often manifests in my life as disappointment. Sometimes, it’s delayed; I realise only decades later that the house, or job or bank balance isn’t what I thought it would be. Sometimes, it’s in the moment: my specific ask to make a donation is met with a hard ‘no’. But either way, I need to realise I didn’t cause each of those outcomes. Although, of course, my choices and actions affected them.

It’s essential for me that I separate people’s beliefs about my actions from a perceived, expected result. Here are some well-meaning encouragements I’ve heard over the years:

‘You’re so confident, so I know you’ll be successful at __________.’

‘You’re tenacious, so I know you won’t give up until you get what you want.’

‘You’re such a good ____________ (writer, public speaker, teacher), so I know the _________ (piece, presentation, class) will go well.’

‘You’ve prepared so much for the interview, so I know you’ll get the job.’

No. You. Don’t.

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not ungrateful for the support. And I don’t discount the first statement. What I’m seeking to disentangle is the causal relationship between the first and the second.

I have two reasons for seeking this disentanglement.

One: phrasing statements this way reinforces a view. A view that I have of myself, but also a view of ‘how the world works’.

This view goes: if you work hard, you get rewarded. If you’re passionate about your work, people will flock to you and pay for, or give to, what you’re selling. If you’re talented, you’ll make it big.

Each time I hear a statement of a fact that is true (‘I am confident’, ‘I am a good writer’, ‘I am focussed and dedicated’) linked to a statement that is a projection (‘therefore this outcome will occur’), I build an expectation. I believe it’s going to happen, because it’s been told to me so many times. And when it doesn’t happen — again and again, it doesn’t happen — I lose confidence, and faith.

In some ways, this loss is helpful, and appropriate. I need to lose confidence: in the false argument, the ‘A, so then B’. But what I don’t need to lose confidence in is the first half of the statement. I am confident. I am a good writer, teacher, public speaker. I am tenacious.

Two: I want to give myself permission to make effort for its own sake. Regardless of the outcome, the effort is worth it in itself. As Oliver Burkeman says, to remove the expectation that all my actions must be great, my actions are freed to have their maximum impact in the context in which they arise.

I don’t mean I always find pleasure in the effort. Particularly in disciplined action — actions made repetitively, over a long period of time — pleasure is fleeting, and joy only occasional. When I meditate regularly, it is boring and expansive and frustrating and spacious. When I write every day, it is uninspiring and euphoric and repetitive and transcendent. I love my job, I hate my job. My marriage is perfect, my marriage is a trap. I have just washed these dishes, why are they dirty again.

I seek out other motivations: satisfaction, pride, clarity. Sometimes it is enough that I have done a task even when I didn’t want to — and found a way to do that without punishing myself, without holding the back of my head to keep my nose to the grindstone.

When our friends reassure us that it will all work out all right in the end, their motivation is pure. But we owe it to ourselves, and them, to interrogate their false assumptions. By focussing on reality — what we can control, what we own (our thoughts, actions and words) — we develop agency and worth.

‘It was meant to be’

The easiest of phrases, it names the feeling of relief when you disappear ambiguity. It’s the joy of naming the moment when everyone gets what they want. Or, in opposite cases, it’s used to explain why we don’t get what we want.

But the reasoning is fundamentally flawed, and fundamentally deluded. It demands we live in the past or the future — negating the present.

First of all, it implies that sometime in the past, a decision was made about what was to be, and all we’re doing now is becoming that.

Second, we trap ourselves into believing an event will definitely happen in the future. We delude ourselves that something has already been decided. Taking solace in the pre-ordained future from a pre-determined past, we step over the discomfort of the unknown, the conditionality of each moment, the opportunity for the unexpected.

It lets us off the hook in the present, because there is some future time that is already pre-ordained, and we can rest in believing it will arrive in its time, separate from any effort on our part.

Just like ‘I always knew you would’, it implies we — or some other force — holds omniscience, and all-seeing power. But how dare we presume to know? We cannot abdicate our responsibility or our effort. Our job is to make the effort, and let the results emerge as they will.

Charlotte Joko Beck: The problem lies not in having goals, but in how we relate to them. We need to have some goals...Having goals is part of being human. It’s the way we do it that creates the trouble.

Student: The best way is to have goals but not cling to the end result?

Joko: That’s right. One simply does what is required to reach the goal...The point is to promote the goal by accomplishing it in the present: doing this, doing that, doing this, as it becomes necessary, right here, right now...

Student: When I set a goal for myself I tend to go into a “fast forward” mode and ignore the flow of the river.

Joko:...Even though we think of the goal as some future state to achieve, the real goal is always the life of this moment, this moment, this moment...there is no way to push the river aside.

- Nothing Special, Living Zen, Charlotte Joko Beck

Work and washing machines

Chevy Chases’s father-in-law pointed out that working hard doesn’t make us special or worthy of praise.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t praise ourselves, our friends, our colleagues. Each day, each moment, one of us acts in a way worthy of rejoicing. Celebrate that. But the celebration of it does not make it singular. We need to recognise that we’re not the only one working pretty damn hard.

But we must not assume that all work, or effort, is of worth — to ourselves or to others. We can question the effort we make, and refine it. William Morris, in his 1889 lecture Useful Work Versus Useless Toil, challenges the (still very contemporary view): ‘It has become an article of the creed of modern morality that all labour is good in itself.’ Instead, he argues there are two kinds of work; one worth doing, one not. One that has hope in it, and the other that does not. But he does not define hope as expectation. Instead, he says:

The nature of the hope which, when it is present, makes work worth doing, is threefold — hope of rest, hope of product, hope of pleasure in the work itself; and hope of these also in some abundance and of good quality.

We cannot work, we cannot make effort, indefinitely. We need to pause; we need to feel the effect of our efforts; and we need to enjoy the effort we have made. He goes on to say:

I think that to all living things there is a pleasure in the exercise of their energies, and that even beasts rejoice in being lithe and swift and strong. But a man at work, making something which he feels will exist because he is working at it and wills it, is exercising the energies of his mind and soul as well as his body. Memory and imagination help him as he works.

Morris advocated for a world in which no one would do any work that ‘cannot be made other than repulsive’, and that ‘if there be any work which cannot be but a torment to the worker, what then? Well, then, let us…leave it undone. The produce of such work cannot be worth the price of it.’

Let’s work, then, and make effort. But we need to stop expecting that this work will produce anything beyond the immediate effect of having made the effort in the first place. And that is as it should be.

Cosmic insignificance therapy

Instead of seeking accolades, approval or achievements, we can rest back in the satisfaction of effort itself. We can experience this as a relief, rather than a disappointment. One way to access this relief is through reflecting on cosmic insignificance. The realisation that, even if our efforts are recognised in some way by some people, that recognition will be fleeting. And even if that effort makes some effect beyond our immediate circle, it will be short-lived. Even if it lasts a bit longer, the effect will likely not outlive us. In that way, we will join the billions of beings who have made effort before us. And leave us free to develop our own confidence in how we spend our time and our energies; trusting that each act has its own weight and effect, worthy in itself.

Oliver Burkeman, recovering positivity guru, explains cosmic insignificance in his book, Four Thousand Weeks.

You almost certainly won’t put a dent in the universe. This realisation isn’t merely calming but liberating…you’re freed to consider the possibility that a far wider variety of things might qualify as meaningful ways to use a finite life.

From this new perspective, it becomes possible to see that preparing nutritious meals for your children might matter as much as anything could ever matter, even if you won’t be winning any cooking awards.

This theory allows us to upend the belief that effort is only worthwhile if its rewarded with greatness, or accolades, or success. Instead, we need to define effort for its own sake.

When we stop looking for the external validation of societally-driven success, we can make internal inquiries instead. How we spend our time, where we put our energies and the effect of our effort on ourselves and those directly around us becomes our focus, and our goal.

We can extricate effort from achievement. By removing the promise of reward, we can settle in to what we feel in our own immediate experience: the satisfaction of exercising the energies of our mind, and our soul.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusory_superiority

These are exactly the kind of thoughts I’ve been trying to keep in mind while doing job applications recently! Particularly the idea that I work hard, and so do other people, so none of us are ‘guaranteed’ a role. There are factors beyond my qualifications at play. You articulated it all so clearly.

I think we have been ordained the same amount of time. I ask myself what it even means to be engaged these days. Engaged with the heart or with the institutions? I don't know but my efforts have all lead me to a very unexpected version of myself.